First there was standard time

For millennia, people have measured time based on the position of the sun; it was noon when the sun was highest in the sky. Sundials were used well into the Middle Ages, at which time mechanical clocks began to appear. Cities would set their town clock by measuring the position of the sun, but every city would be on a slightly different time.

For millennia, people have measured time based on the position of the sun; it was noon when the sun was highest in the sky. Sundials were used well into the Middle Ages, at which time mechanical clocks began to appear. Cities would set their town clock by measuring the position of the sun, but every city would be on a slightly different time.

The time indicated by the apparent sun on a sundial is called Apparent Solar Time, or true local time. The time shown by the fictitious sun is called Mean Solar Time, or local mean time when measured in terms of any longitudinal meridian.

[For more information about clocks, see A Walk through Time.]

Standard time begins in Britain

Britain was the first country to set the time throughout a region to one standard time. The railways cared most about the inconsistencies of local mean time, and they forced a uniform time on the country. The original idea was credited to Dr. William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828) and was popularized by Abraham Follett Osler (1808-1903). The Great Western Railway was the first to adopt London time, in November 1840. Other railways followed suit, and by 1847 most (though not all) railways used London time. On September 22, 1847, the Railway Clearing House, an industry standards body, recommended that GMT be adopted at all stations as soon as the General Post Office permitted it. The transition occurred on December 1 for the L&NW, the Caledonian, and presumably other railways; the January 1848 Bradshaw's lists many railways as using GMT. By 1855, the vast majority of public clocks in Britain were set to GMT (though some, like the great clock on Tom Tower at Christ Church, Oxford, were fitted with two minute hands, one for local time and one for GMT). The last major holdout was the legal system, which stubbornly stuck to local time for many years, leading to oddities like polls opening at 08:13 and closing at 16:13. The legal system finally switched to GMT when the Statutes (Definition of Time) Act took effect; it received the Royal Assent on August 2, 1880.

Standard time in the US

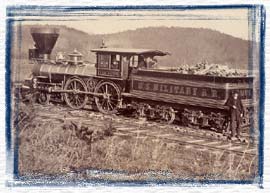

Standard time in time zones was instituted in the U.S. and Canada by the railroads on November 18, 1883. Prior to that, time of day was a local matter, and most cities and towns used some form of local solar time, maintained by a well-known clock (on a church steeple, for example, or in a jeweler's window). The new standard time system was not immediately embraced by all, however. (The train at right is a Union locomotive used during the American Civil War, photo ca. 1861-1865.)

The first man in the United States to sense the growing need for time standardization was an amateur astronomer, William Lambert, who as early as 1809 presented to Congress a recommendation for the establishment of time meridians. This was not adopted, nor was the initial suggestion of Charles Dowd of Saratoga Springs, N.Y., in 1870. Dowd revised his proposal in 1872, and it was adopted virtually unchanged by U.S. and Canadian railways eleven years later.

Detroit kept local time until 1900, when the City Council decreed that clocks should be put back 28 minutes to Central Standard Time. Half the city obeyed, while half refused. After considerable debate, the decision was rescinded and the city reverted to sun time. A derisive offer to erect a sundial in front of the city hall was referred to the Committee on Sewers. Then, in 1905, Central Standard Time was adopted by city vote.

It remained for a Canadian civil and railway engineer, Sandford Fleming, to instigate the initial effort that led to the adoption of the present time meridians in both Canada and the U.S. Time zones were first used by the railroads in 1883 to standardize their schedules. Canada's Sir Sandford Fleming (posing at left, at the driving the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Sandford Fleming wears the stovepipe hat and is to the left of the man with the hammer) also played a key role in the development of a worldwide system of keeping time. Trains had made the old system - where major cities and regions set clocks according to local astronomical conditions - obsolete. Fleming advocated the adoption of a standard or mean time and hourly variations from that according to established time zones. He was instrumental in convening the 1884 International Prime Meridian Conference in Washington, at which the system of international standard time - still in use today - was adopted.

It remained for a Canadian civil and railway engineer, Sandford Fleming, to instigate the initial effort that led to the adoption of the present time meridians in both Canada and the U.S. Time zones were first used by the railroads in 1883 to standardize their schedules. Canada's Sir Sandford Fleming (posing at left, at the driving the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Sandford Fleming wears the stovepipe hat and is to the left of the man with the hammer) also played a key role in the development of a worldwide system of keeping time. Trains had made the old system - where major cities and regions set clocks according to local astronomical conditions - obsolete. Fleming advocated the adoption of a standard or mean time and hourly variations from that according to established time zones. He was instrumental in convening the 1884 International Prime Meridian Conference in Washington, at which the system of international standard time - still in use today - was adopted.

The use of standard time gradually increased because of its obvious practical advantages for communication and travel. Standard time in time zones was established by U.S. law with the Standard Time Act of 1918, enacted on March 19. Congress adopted standard time zones based on those set up by the railroads, and gave the responsibility to make any changes in the time zones to the Interstate Commerce Commission, the only federal transportation regulatory agency at the time. When Congress created the Department of Transportation in 1966, it transferred the responsibility for the time laws to the new department.

Time zone boundaries have changed greatly since their original introduction and changes still occasionally occur. The Department of Transportation conducts rulemakings to consider requests for changes. Generally, time zone boundaries have tended to shift westward. Places on the eastern edge of a time zone can effectively move sunset an hour later (by the clock) by shifting to the time zone immediately to their east. If they do so, the boundary of that zone is locally shifted to the west; the accumulation of such changes results in the long-term westward trend. The process is not inexorable, however, since the late sunrises experienced by such places during the winter may be regarded as too undesirable. Furthermore, under the law, the principal standard for deciding on a time zone change is the "convenience of commerce." Proposed time zone changes have been both approved and rejected based on this criterion, although most such proposals have been accepted.

Time zone boundaries have changed greatly since their original introduction and changes still occasionally occur. The Department of Transportation conducts rulemakings to consider requests for changes. Generally, time zone boundaries have tended to shift westward. Places on the eastern edge of a time zone can effectively move sunset an hour later (by the clock) by shifting to the time zone immediately to their east. If they do so, the boundary of that zone is locally shifted to the west; the accumulation of such changes results in the long-term westward trend. The process is not inexorable, however, since the late sunrises experienced by such places during the winter may be regarded as too undesirable. Furthermore, under the law, the principal standard for deciding on a time zone change is the "convenience of commerce." Proposed time zone changes have been both approved and rejected based on this criterion, although most such proposals have been accepted.

|

|

|

| Page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | ||