American Abstract Expressionism: Painting Action and Colorfields

In the 1940s and the 1950s, American artists become known for their new vision, called Abstract Expressionism. The group includes artists such as Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), Lee Krasner (1908-1984), Willem and Elaine de Kooning (1904-1997, 1920-1989), Mark Rothko (1903-1970), Barnett Newman (1905-1970), Ad Reinhardt (1913-1967), Robert Motherwell (1915-1991), and Norman Lewis (1909-1979).

Autumn Rhythm No. 30, Jackson Pollock, 1950. Pollock revealed the life of a painting through “actions,” a technique of dripping and pouring paint on a canvas that is placed directly on the floor.

Jackson Pollock’s art conveys the mindset of Abstract Expressionism. Pollock argued, “The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through”. Pollock reveals the life of the painting through “actions,” an energetic technique of dripping and pouring paint on a canvas that is placed directly on the floor. Pollock explained, “On the floor I am more at ease, I feel nearer, more a part of the painting… Since this way I can walk around in it… Work from the four sides and be literally ‘in’ the painting.”

Pollock abandons traditional composition. His works do not have any points of emphasis or identifiable parts. They also lack a central motif. Therefore, the spectator’s eye is continuously on the move. Pollock’s approach encourages the spectator’s peripheral vision. Action paintings are perceived as vital and dynamic because our gaze cannot settle or focus on the canvas.

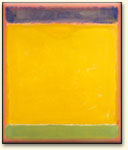

Mark Rothko’s technique of painting departs from Pollock’s actions. Rothko’s style is called colorfield painting. His works consist of strong formal elements, such as color, shape, balance, depth, composition, and scale. They confirm the ideas of the formalist critic Clement Greenberg, who suggested in “Modernist Painting” (1960) that artists should respect the limitations of each media. Because a canvas is a two-dimensional surface, painting should avoid any illusion of three-dimensional representation.

Even so, Rothko refused to be considered solely in these terms, arguing, “It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academic painting…. However, there is no such thing as good painting about nothing”. Rothko believed that while flat, two-dimensional forms destroyed illusion, they also revealed truth.

What is the truth that Rothko attempted to reveal? The titles of his paintings offer few answers, as Rothko begins to abandon conventional titles in 1947. Some critics have suggested that Rothko’s works refer to Western American landscape. However, Rothko declared that there was no “landscape” in his art. Instead, Rothko argued that his paintings are “fully visible” to the viewer. They do not refer to anything else. In other words, what you see is what you get. Ideally, the viewer would stand in front of his paintings, focusing on large fields of color and abstract forms, and come to terms with the self and his or her own scale. Colorfield painters believe that art could encourage the physical sensation of time and being there with the work.

Untitled (Seagram Mural), Mark Rothko, c. 1958. Does this painting encourage a different physical sensation than his work, Blue, Yellow, Green on Red pictured above?

Rothko’s early palette consists of bright colors. However, his colors begin to darken dramatically during the late 1950s. Increasingly, Rothko uses red, maroon, brown, and black. Also, his motifs change from an open to a closed form. Because his paintings do not have any given subject matter, this change of color and form is crucial. Consider how Rothko’s darkened colors and closed forms affect the mood of his works. Does Rothko’s Untitled (Seagram Mural, c. 1958) encourage a different physical sensation of time and being there with the work than his Blue, Yellow, Green on Red (1954)?