What Happens in the Eye?

The eye is often compared to a camera. But it might be more appropriate to compare it to a TV camera that is self-focusing, has a self-cleaning lens and has its images processed by a computer with millions of CPUs.

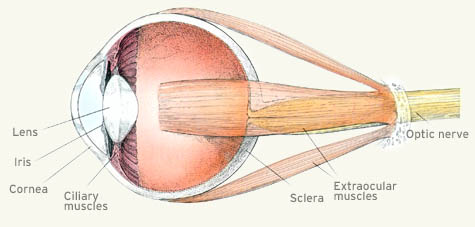

When our eye sees, light from the outside world is focused by the lens onto the retina. There, it is absorbed by pigments in light-sensitive cells, called rods and cones.

Many animals have two different types of cones. (Some, like birds have five or more.) Higher primates, including humans, have three different types.

Scanning electron micrograph of rods and cones. The rods are cylindrical in shape, while the cones are conical in shape. |

Visual pigments have similar amino acids sequences. The colored dots above represent amino acids that differ. The bottom right shows the slight difference between the long and medium pigments. |

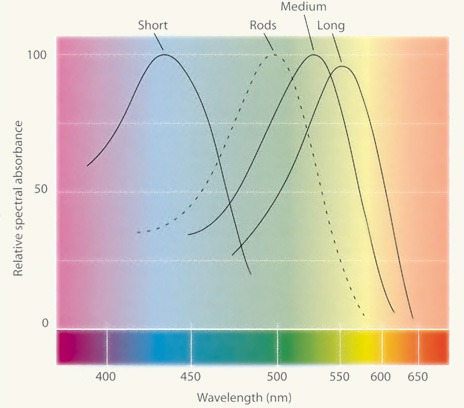

There are approximately 6 million cones in our retina, and they are sensitive to a wide range of brightness. The three different types of cones are sensitive to short, medium and long wavelengths, respectively, shown in the figure below. (Additionally, we have approximately 125 million rods on the retina, which are used only in dim light, and are monochromatic – black and white.)

This graph shows the sensitivity of the different cones to varying wavelengths. The graph shows how the response varies by wavelength for each kind of receptor.

For example, the medium cone is more sensitive to pure green wavelengths than to red wavelengths.

It is interesting to note that the existence of such receptors was first hypothesized by George Palmer in 1777, and more famously a few decades later by Thomas Young, but not actually discovered until the late 19th century.