Paleolithic Art in the Roucadour cave

Roucadour cave, Themines, Quercy, Lot, France.

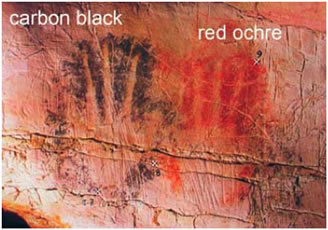

A picture of negative hands in the Roucadour cave made of carbon black and red ochre. The cave of Roucadour is a large cavity with easy access, formed by a steep descending main gallery (15-20 m wide; 15 m high) and a lateral gallery (40 m long). The figures are at the end of the lateral gallery, 6 m above the present floor level. The cave is particularly rich in engravings, realistic as stylized animal figures and geometric and ‘ritualistic’ signs (vertical and circular signs). The paintings and engravings in the Roucadour cave, France, are attributed to the oldest phase of Paleolithic Art in Quercy, between 28,000 and 24,000 years BP. The paintings are limited to negative hands (a dozen human hands painted in black (carbon black) or in red (red ochre) and to some painted engravings.

Painting techniques

The first paintings were cave paintings. Ancient peoples decorated walls of protected caves with paint made from dirt or charcoal mixed with spit or animal fat. In cave paintings, the pigments stuck to the wall partially because the pigment became trapped in the porous wall, and partially because the binding media (the spit or fat) dried and adhered the pigment to the wall.

Historians hypothesize that paint was applied with brushing, smearing, dabbing, and spraying techniques. Large areas were covered with fingertips or pads of lichen or moss. Twigs produced drawn or linear marks, while feathers blended areas of color. Brushes made from horsehair were used for paint application and outlining. Paint spraying, accomplished by blowing paint through hollow bones, yielded a finely grained distribution of pigment, similar to an airbrush. The oxides of iron dug right out of the ground in the form of lumps were presumably rich in clay. This consistency was conducive to the formation of crayon sticks and also could be made into a liquid paste more closely resembling paint. Historians believe that the lumps were ground into a fine powder on the cave’s natural stone hollows, where stains have been observed. Shoulder and other bones of large animals, stained with color, have been discovered in the caves and presumed to have been used as mortars for pigment grinding. The pigment was made into a paste with various binders, including water, vegetable juices, urine, animal fat, bone marrow, blood, and albumen.

The palette

Prehistoric painters used the pigments available in the vicinity. These pigments were the so-called earth pigments, (minerals limonite and hematite, red ochre, yellow ochre and umber), charcoal from the fire (carbon black), burnt bones (bone black) and white from grounded calcite (lime white).

Indeed, Prehistoric dwellers may have discovered that, unlike the dye colors they were using and which were derived from animal and vegetable sources, the color that came from iron oxide deposits in the earth would not fade with the changing environment. For this reason, it is believed that men traveled far and wide to maintain a steady supply of earth pigments. In every locality where prehistoric sites have been discovered, from Texas to South Africa, trails lead to near and distant hematite deposits where man mined. Historians have deduced that the impetus behind all mining activities was prehistoric man’s need for ochre pigments. Cave men might have traveled as far as 25 miles to obtain iron earth pigments for their paint in the Lascaux area.