Wild Beasts and Colors

In the early 20th century, art underwent momentous changes. Artists became increasingly interested in non-naturalistic representation, departing from the traditional use of form and color. From 1904, the Fauve artists, including Henri Matisse (1869-1954), André Derain (1880-1954), Raoul Dufy (1877-1953), Henri Manguin (1874-1949), Maurice Vlaminck (1876-1958) and Georges Braque (1882-1963), begin to portray familiar objects with “unfamiliar” colors. The French term “fauvism” refers to “wild beasts.” However, a better name for the group might be “the artists of pure color.” Fauvism is the first modern movement in which color rules supreme. Why and how did these artists depart from naturalistic colors?

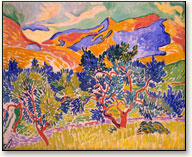

Mountains at Collioure, André Derain, 1905. The trees and grass are drawn with long strokes of pure color. However, for both Derain and Matisse, color was a less emotional, less personal imperative than it had been for van Gogh. |

Open Window, Collioure, Henri Matisse, 1905. This is among the very first Fauve works. It was painted during the summer of 1905, when Matisse, together with André Derain, worked in the small Mediterranean fishing port of Collioure, near the Spanish border. |

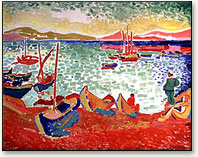

Boats in the Port of Collioure, André Derain, 1905. With its vivid colors and broken brushwork, this painting is highly typical of the style known as Fauvism.

According to Matisse, “Fauve art isn’t everything, but it is the foundation of everything.” However, contemporary spectators did not always understand Matisse’s aims and were outraged by Fauve paintings. Why were they so shocked?

Even if the subject matter of the Fauve painting is often traditional (for example, a portrait, a nude, a landscape or an interior), the Fauve colors were something different. The Fauve colors seemed bright and unnatural, even assaulting to the eye. Also, the fragmented way that they were applied — in larger and smaller blocks — made the pictures seem sketchy, clumsy and unfinished to their contemporary audience. The spectator identifies the form to be “right” and the color to be “wrong.”

In traditional art, both form and color are “right” or representational. The artist starts with form and the form determines the color. Color follows form; the artist cannot start with color. The traditional artist cannot use color alone as a means of expression.

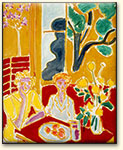

Two Girls in a Yellow and Red Interior, Henri Matisse, 1947.

Matisse’s expressive use liberated color, so that it is no longer determined by form. His color looks for a sensation that represents his subjective vision and state of mind. Therefore, it could be unnatural or non-representational. For the spectator, Matisse’s form may seem right but his color may seem wrong, because it is not used to convey likeness, but rather sensation. As Matisse put it, “When I put a green, it is not grass. When I put a blue, it is not the sky.”

Even today, the spectator of Matisse’s work senses the intensity achieved by color. Does the afternoon sun in Matisse’s Boats in the Port of Collioure (above) look bright to you? Which of the colors are right? Which are wrong? The shore should not be red. Nor the sea green. Using his intuition, Matisse created the effect of a spring sky with complicated color combinations and luminance.

Red Studio, Henri Matisse, 1911.

Neuroscientifically, Matisse’s paintings work like a black and white photograph. Although the photograph lacks color, our brains are able to recognize the depicted elements because our minds react to the unnaturalistic colors using one visual pathway. Even if we perceive the color as wrong, to other visual pathways that are solely monochromatic, the scene seems more right. This principle of discussing color in terms of right and wrong helps us to understand Matisse’s work. Even so, it is important to remember that Matisse never discusses his work in these terms. For him, it does not matter whether color is right, because color reflects his subjective inner vision. Therefore, color is always right to Matisse, since it responds to his artistic perception.

A few years later, the Cubists, led by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), liberated form, contributing to the development of modern art. Their work suggests an illusion of four-dimensional space, in which the subject is seen simultaneously from multiple perspectives, opposing the traditional three-dimensional view to the world. Even so, the subject of the Cubist painting is still identifiable. Although the Fauvists and the Cubists are not interested in depicting abstraction, their departure from the traditional use of form and color is important to the development of abstract painting, where these two elements — form and color — become fully independent from the depicted subject. Therefore, instead of a naturalistic illusion, modern art often represents the artist’s subjective sensation.